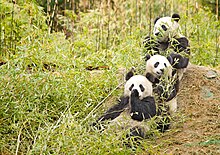

The giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), also known as the panda bear or simply panda, is a bear species endemic to China. It is characterised by its white coat with black patches around the eyes, ears, legs and shoulders. Its body is rotund; adult individuals weigh 100 to 115 kg (220 to 254 lb) and are typically 1.2 to 1.9 m (3 ft 11 in to 6 ft 3 in) long. It is sexually dimorphic, with males being typically 10 to 20% larger than females. A thumb is visible on its forepaw, which helps in holding bamboo in place for feeding. It has large molar teeth and expanded temporal fossa to meet its dietary requirements. It can digest starch and is mostly herbivorous with a diet consisting almost entirely of bamboo and bamboo shoots.

The giant panda lives exclusively in six montane regions in a few Chinese provinces at elevations of up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft). It is solitary and gathers only in mating seasons. It relies on olfactory communication to communicate and uses scent marks as chemical cues and on landmarks like rocks or trees. Females rear cubs for an average of 18 to 24 months. The oldest known giant panda was 38 years old.

As a result of farming, deforestation and infrastructural development, the giant panda has been driven out of the lowland areas where it once lived. The wild population has increased again to 1,864 individuals as of March 2015. Since 2016, it has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. In July 2021, Chinese authorities also classified the giant panda as vulnerable. It is a conservation-reliant species. By 2007, the captive population comprised 239 giant pandas in China and another 27 outside the country. It has often served as China’s national symbol, appeared on Chinese Gold Panda coins since 1982 and as one of the five Fuwa mascots of the 2008 Summer Olympics held in Beijing.

Etymology

The word panda was borrowed into English from French, but no conclusive explanation of the origin of the French word panda has been found.[3] The closest candidate is the Nepali word ponya, possibly referring to the adapted wrist bone of the red panda, which is native to Nepal. In many older sources, the name “panda” or “common panda” refers to the red panda (Ailurus fulgens),[4] which was described some 40 years earlier and over that period was the only animal known as a panda.[5] The binomial name Ailuropoda melanoleuca means black and white (melanoleuca) cat-foot (ailuropoda).[6]

Since the earliest collection of Chinese writings, the Chinese language has given the bear many different names, including mò (貘, ancient Chinese name for giant panda),[7] huāxióng (花熊; “spotted bear”) and zhúxióng (竹熊; “bamboo bear”).[8] The most popular names in China today are dàxióngmāo (大熊貓; lit. ’giant bear cat’), or simply xióngmāo (熊貓; lit. ’bear cat’). As with the word panda in English, xióngmāo (熊貓) was originally used to describe just the red panda, but dàxióngmāo (大熊貓) and xiǎoxióngmāo (小熊猫; lit. ’little bear cat’) were coined to differentiate between the species.[8]

In Taiwan, another popular name for panda is the inverted dàmāoxióng (大貓熊; lit. ’giant cat bear’), though many encyclopedias and dictionaries in Taiwan still use the “bear cat” form as the correct name. Some linguists argue, in this construction, “bear” instead of “cat” is the base noun, making the name more grammatically and logically correct, which have led to the popular choice despite official writings.[8] This name did not gain its popularity until 1988, when a private zoo in Tainan painted a sun bear black and white and created the Tainan fake panda incident.[9][10]

Taxonomy

For many decades, the precise taxonomic classification of the giant panda was under debate because it shares characteristics with both bears and raccoons.[11] In 1985, molecular studies indicated that the giant panda is a true bear, part of the family Ursidae.[12][13] These studies show it diverged about 19 million years ago from the common ancestor of the Ursidae;[14] it is the most basal member of this family and equidistant from all other extant bear species.[14][15]

Subspecies

Two subspecies of giant panda have been recognized on the basis of distinct cranial measurements, colour patterns, and population genetics.[16]

- The nominate subspecies, A. m. melanoleuca, consists of most extant populations of the giant panda. These animals are principally found in Sichuan and display the typical stark black and white contrasting colours.[17]

- The Qinling panda, A. m. qinlingensis,[18] is restricted to the Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi at elevations of 1,300–3,000 m (4,300–9,800 ft). The typical black and white pattern of Sichuan giant pandas is replaced with a light brown and white pattern.[16] The skull of A. m. qinlingensis is smaller than its relatives, and it has larger molars.[19]

A detailed study of the giant panda’s genetic history from 2012 confirms that the separation of the Qinling population occurred about 300,000 years ago, and reveals that the non-Qinling population further diverged into two groups, named the Minshan and the Qionglai–Daxiangling–Xiaoxiangling–Liangshan group respectively, about 2,800 years ago.[20]

Phylogeny

Of the eight extant species in the bear family Ursidae, the giant panda’s lineage branched off the earliest.[21][22]

| Ursidae | Giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) Spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) Ursinae (black, brown, sloth, sun, and polar bears) |

Distribution and habitat

The giant panda is endemic to China. It is found in small, fragmented populations in six mountainous regions in the country, mainly in Sichuan, and also in neighbouring Shaanxi and Gansu.[23] Successful habitat preservation has seen a rise in panda numbers, though loss of habitat due to human activities remains its biggest threat. In areas with a high concentration of medium-to-large-sized mammals—such as domestic cattle, a species known to degrade the landscape—the giant panda population is generally low. This is mainly attributed to the panda’s avoidance of interspecific competition.[24][25]

The species has been located at elevations of 2,400 to 3,000 m (7,900 to 9,800 ft) above sea level.[26] They frequent habitats with a healthy concentration of bamboos, typically old-growth forests, but may also venture into secondary forest habitats.[27] The Daxiangling Mountain population inhabits both coniferous and broadleaf forests.[28] Additionally, the Qinling population often selects evergreen broadleaf and conifer forests, while pandas in the Qionglai mountainous region exclusively select upland conifer forests. The remaining two populations, namely those occurring in the Liangshan and Xiaoxiangling mountains, predominantly occur in broadleaf evergreen and conifer forests.[12]: 137–148

Giant pandas once roamed across Southeast Asia from Myanmar to northern Vietnam. Their range in China spanned much of the southeast region. By the Pleistocene, climate change affected panda populations, and the subsequent domination of modern humans led to large-scale habitat loss.[29][30] In 2001, it was estimated that the range of the giant panda had declined by about 99% of its range in earlier millenniums.[31]

Description

The skull of a giant panda at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History

Close-up of giant panda at ZooParc in Beauval, France

The giant panda has a body shape typical of bears. It has black fur on its ears, limbs, shoulders and around the eyes. The rest of the animal’s coat is white.[32] The bear’s distinctive coloration appears to serve as camouflage in both winter and summer environments as they do not hibernate. The white areas serve as camouflage in snow, while the black shoulders and legs conceal them in shade.[33] Studies in the wild have found that when viewed from a distance, the panda displays disruptive coloration, while up close, they rely more on blending in.[34] The black ears may be used to display aggression,[33] while the eye patches might facilitate them identifying one another.[33][35] The giant panda’s thick, woolly coat keeps it warm in the cool forests of its habitat.[32]

The panda’s skull shape is typical of durophagous carnivorans. It has evolved from previous ancestors to exhibit larger molars with increased complexity and expanded temporal fossa.[36][37] A study revealed that a 117.5 kg (259 lb) giant panda had a bite force of 1298.9 Newton (BFQ 151.4) at canine teeth and 1815.9 Newton (BFQ 141.8) at carnassial teeth.[38] Adults measure around 1.2 to 1.9 m (3 ft 11 in to 6 ft 3 in) long, including a tail of about 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in), and 60 to 90 cm (24 to 35 in) tall at the shoulder.[39][40] Males can weigh up to 160 kg (350 lb).[41] Females are generally 10–20% smaller than males.[42] They weigh between 70 kg (150 lb) and 125 kg (276 lb).[43][39][44] The average weight for adults is 100 to 115 kg (220 to 254 lb).[45]

The giant panda’s paw has a digit similar to a thumb and five fingers; the thumb-like digit – actually a modified sesamoid bone – helps it to hold bamboo while eating.[46][47] The giant panda’s tail, measuring 10 to 15 cm (3.9 to 5.9 in), is the second-longest in the bear family, behind the sloth bear.[42]

Ecology

Diet

Duration: 34 seconds.0:34Subtitles available.CCPandas eating, standing, and playing

Despite its taxonomic classification as a carnivoran, the giant panda’s diet is primarily herbivorous, with approximately 99% of its diet consisting of bamboo.[48] However, the giant panda still has the digestive system of a carnivore, as well as carnivore-specific genes,[49] and thus derives little energy and little protein from the consumption of bamboo. The ability to break down cellulose and lignin is very weak, and their main source of nutrients comes from starch and hemicelluloses. The most important part of their bamboo diet is the shoots, that are rich in starch and have up to 32% protein content. Accordingly, pandas have evolved a higher capability to digest starches than strict carnivores.[50] Raw bamboo is toxic, containing cyanide compounds. Pandas’ body tissues are less able than herbivores to detoxify cyanide, but their gut microbiomes are significantly enriched in putative genes coding for enzymes related to cyanide degradation, suggesting that they have cyanide-digesting gut microbes.[51] It has been estimated that an adult panda absorbs 54.8–66.1 mg (0.846–1.020 gr) of cyanide a day through its diet. To prevent poisoning, they have evolved anti-toxic mechanisms to protect themselves. About 80% of the cyanide is metabolized to less toxic thiocyanate and discharged in urine, while the remaining 20% is detoxified by other minor pathways.[52]

During the shoot season (April–August), pandas store a large amount of food in preparation for the months succeeding this seasonal period, in which pandas live off a diet of bamboo leaves.[53] The giant panda is a highly specialised animal with unique adaptations, and has lived in bamboo forests for millions of years.[54] The average giant panda eats as much as 9 to 14 kg (20 to 31 lb) of bamboo shoots a day to compensate for the limited energy content of its diet. Ingestion of such a large quantity of material is possible and necessary because of the rapid passage of large amounts of indigestible plant material through the short, straight digestive tract.[55][56] It is also noted, however, that such rapid passage of digesta limits the potential of microbial digestion in the gastrointestinal tract,[55] limiting alternative forms of digestion. Given this voluminous diet, the giant panda defecates up to 40 times a day.[57] The limited energy input imposed on it by its diet has affected the panda’s behavior. The giant panda tends to limit its social interactions and avoids steeply sloping terrain to limit its energy expenditures.[58]

Two of the panda’s most distinctive features, its large size and round face, are adaptations to its bamboo diet. Anthropologist Russell Ciochon observed: “[much] like the vegetarian gorilla, the low body surface area to body volume [of the giant panda] is indicative of a lower metabolic rate. This lower metabolic rate and a more sedentary lifestyle allows the giant panda to subsist on nutrient poor resources such as bamboo.”[58] The giant panda’s round face is the result of powerful jaw muscles, which attach from the top of the head to the jaw.[58] Large molars crush and grind fibrous plant material.[59]

The morphological characteristics of extinct relatives of the giant panda suggest that while the ancient giant panda was omnivorous 7 million years ago (mya), it only became herbivorous some 2–2.4 mya with the emergence of A. microta.[59][60] Genome sequencing of the giant panda suggests that the dietary switch could have initiated from the loss of the sole umami taste receptor, encoded by the genes TAS1R1 and TAS1R3 (also known as T1R1 and T1R3), resulting from two frameshift mutations within the T1R1 exons.[49] Umami taste corresponds to high levels of glutamate as found in meat and may have thus altered the food choice of the giant panda.[61] Although the pseudogenisation (conversion into a pseudogene) of the umami taste receptor in Ailuropoda coincides with the dietary switch to herbivory, it is likely a result of, and not the reason for, the dietary change.[59][49][61] The mutation time for the T1R1 gene in the giant panda is estimated to 4.2 mya[59] while fossil evidence indicates bamboo consumption in the giant panda species at least 7 mya,[60] signifying that although complete herbivory occurred around 2 mya, the dietary switch was initiated prior to T1R1 loss-of-function.[62]

Pandas eat any of 25 bamboo species in the wild, with the most common including Fargesia dracocephala[62] and Fargesia rufa.[63] Only a few bamboo species are widespread at the high altitudes pandas now inhabit. Bamboo leaves contain the highest protein levels; stems have less.[64] Because of the synchronous flowering, death, and regeneration of all bamboo within a species, the giant panda must have at least two different species available in its range to avoid starvation. While primarily herbivorous, the giant panda still retains decidedly ursine teeth and will eat meat, fish, and eggs when available. In captivity, zoos typically maintain the giant panda’s bamboo diet, though some will provide specially formulated biscuits or other dietary supplements.[65]

Pandas will travel between different habitats if they need to, so they can get the nutrients that they need and to balance their diet for reproduction.[66]

Interspecific interactions

Although adult giant pandas have few natural predators other than humans, young cubs are vulnerable to attacks by snow leopards, yellow-throated martens,[67] eagles, feral dogs, and the Asian black bear. Sub-adults weighing up to 50 kg (110 lb) may be vulnerable to predation by leopards.[68]

Giant pandas are sympatric with other large mammals and bamboo feeders, such as the takin (Budorcas taxicolor). The takin and giant panda share a similar ecological niche, and they consume the same resources. When competition for food is fierce, pandas disperse to the outskirts of takin distribution. Other possible competitors include but is not limited to, the Eurasian wild pig (Sus scrofa), Chinese goral (Naemorhedus griseus) and the Asian black bear (Ursus thibetanus). Giant pandas avoid areas with a mid-to-high density of livestock, as they depress the vegetation.[69] The Tibetan Plateau is the only known area where both giant and red pandas can be found. Although sharing near-identical ecological niches, competition between the two species has rarely been observed. Nearly 50% of their respective distribution overlaps, and successful coexistence is achieved through distinct habitat selection.[70]

Pathogens and parasites

A captive female died from toxoplasmosis, a disease caused by an obligate intracellular parasitic protozoan known as Toxoplasma gondii that infects most warm-blooded animals, including humans.[71] They are likely susceptible to diseases from Baylisascaris schroederi, a parasitic nematode known to infect giant panda intestines. This nematode species is known to give pandas baylisascariasi, a deadly disease that kills more wild pandas than any other cause. Additionally, the population is threatened by canine distemper virus (CDV), canine parvovirus, rotavirus, canine adenovirus, and canine coronavirus. Bacteria, such as Clostridium welchii, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli, may also be lethal.[72]

Behavior

The giant panda is a terrestrial animal and primarily spends its life roaming and feeding in the bamboo forests of the Qinling Mountains and in the hilly province of Sichuan.[73] Giant pandas are generally solitary.[54] Each adult has a defined territory and a female is not tolerant of other females in her range. Social encounters occur primarily during the brief breeding season in which pandas in proximity to one another will gather.[74] After mating, the male leaves the female alone to raise the cub.[32] Pandas were thought to fall into the crepuscular category, those who are active twice a day, at dawn and dusk; however, pandas may belong to a category all of their own, with activity peaks in the morning, afternoon and midnight. The low nutrition quality of bamboo means pandas need to eat more frequently, and due to their lack of major predators they can be active at any time of the day.[75] Activity is highest in June and decreases in late summer to autumn with an increase from November through the following March.[76] Activity is also directly related to the amount of sunlight during colder days.[76] There is a significant interaction of solar radiation, such that solar radiation has a stronger positive effect on activity levels of panda bears.[76]

Pandas communicate through vocalisation and scent marking such as clawing trees or spraying urine.[43] They are able to climb and take shelter in hollow trees or rock crevices, but do not establish permanent dens. For this reason, pandas do not hibernate, which is similar to other subtropical mammals, and will instead move to elevations with warmer temperatures.[77] Pandas rely primarily on spatial memory rather than visual memory.[78] Though the panda is often assumed to be docile, it has been known to attack humans on rare occasions.[79][80][81] Pandas have been known to cover themselves in horse manure to protect themselves against cold temperatures.[82]

The species communicates foremost through a blatting sound; they achieve peaceful interactions through the emission of this sound. When in oestrus, a female emits a chirp. In hostile confrontations or during fights, the giant panda emits vocalizations such as a roar or growl. On the other hand, squeals typically indicate inferiority and submission in a dispute. Other vocalizations include honks and moans.[83]

Olfactory communication

Giant pandas heavily rely on olfactory communication to communicate with one another. Scent marks are used to spread these chemical cues and are placed on landmarks like rocks or trees.[84] Chemical communication in giant pandas plays many roles in their social situations. Scent marks and odors are used to spread information about sexual status, whether a female is in estrus or not, age, gender, individuality, dominance over territory, and choice of settlement.[84] Giant pandas communicate by excreting volatile compounds, or scent marks, through the anogenital gland.[84][85] Giant pandas have unique positions in which they will scent mark. Males deposit scent marks or urine by lifting their hind leg, rubbing their backside, or standing in order to rub the anogenital gland onto a landmark. Females, however, exercise squatting or simply rubbing their genitals onto a landmark.[84][86]

The season plays a major role in mediating chemical communication.[87] Depending on the season, mainly whether it is breeding season or not, may influence which odors are prioritized. Chemical signals can have different functions in different seasons. During the non-breeding season, females prefer the odors of other females because reproduction is not their primary motivation. However, during breeding season, odors from the opposite sex will be more attractive.[87][88] Because they are solitary mammals and their breeding season is so brief, female pandas secrete chemical cues in order to let males know their sexual status.[88] The chemical cues female pandas secrete can be considered to be pheromones for sexual reproduction.[88] Females deposit scent marks through their urine which induces an increase in androgen levels in males.[88] Androgen is a sex hormone found in both males and females; testosterone is the major androgen produced by males. Civetone and decanoic acid are chemicals found in female urine which promote behavioral responses in males; both chemicals are considered giant panda pheromones.[88] Male pandas also secrete chemical signals that include information about their sexual reproductivity and age, which is beneficial for a female when choosing a mate.[84][87] For example, age can be useful for a female to determine sexual maturity and sperm quality.[89] Pandas are also able to determine when the signal was placed, further aiding in the quest to find a potential mate.[89] However, chemical cues are not just used for communication between males and females, pandas can determine individuality from chemical signals. This allows them to be able to differentiate between a potential partner or someone of the same sex, which could be a potential competitor.[89]

Chemical cues, or odors, play an important role in how a panda chooses their habitat. Pandas look for odors that tell them not only the identity of another panda, but if they should avoid them or not.[89] Pandas tend to avoid their species for most of the year, breeding season being the brief time of major interaction.[89] Chemical signaling allows for avoidance and competition.[86][87] Pandas whose habitats are in similar locations will collectively leave scent marks in a unique location which is termed “scent stations”.[89] When pandas come across these scent stations, they are able to identify a specific panda and the scope of their habitat. This allows pandas to be able to pursue a potential mate or avoid a potential competitor.[89]

Pandas can assess an individual’s dominance status, including their age and size, via odor cues and may choose to avoid a scent mark if the signaler’s competitive ability outweighs their own.[86] A panda’s size can be conveyed through the height of the scent mark.[86][90] Since larger animals can place higher scent marks, an elevated scent mark advertises a higher competitive ability. Age must also be taken into consideration when assessing a competitor’s fighting ability. For example, a mature panda will be larger than a younger, immature panda and possess an advantage during a fight.[86]

Reproduction

Giant pandas reach sexual maturity between the ages of four and eight, and may be reproductive until age 20.[91] The mating season is between March and May, when a female goes into estrus, which lasts for two or three days and only occurs once a year.[92] When mating, the female is in a crouching, head-down position as the male mounts her from behind. Copulation time ranges from 30 seconds to five minutes, but the male may mount her repeatedly to ensure successful fertilisation. The gestation period is somewhere between 95 and 160 days – the variability is due to the fact that the fertilized egg may linger in the reproductive system for a while before implanting on the uterine wall.[92] Giant pandas give birth to twins in about half of pregnancies.[93] If twins are born, usually only one survives in the wild. The mother will select the stronger of the cubs, and the weaker cub will die due to starvation. The mother is thought to be unable to produce enough milk for two cubs since she does not store fat.[94] The father has no part in helping raise the cub.[32]

When the cub is first born, it is pink, blind, and toothless,[32] weighing only 90 to 130 g (3.2 to 4.6 oz), or about 1/800 of the mother’s weight,[11] proportionally the smallest baby of any placental mammal.[95] It nurses from its mother’s breast six to 14 times a day for up to 30 minutes at a time. For three to four hours, the mother may leave the den to feed, which leaves the cub defenseless. One to two weeks after birth, the cub’s skin turns grey where its hair will eventually become black. Slight pink colour may appear on the cub’s fur, as a result of a chemical reaction between the fur and its mother’s saliva. A month after birth, the colour pattern of the cub’s fur is fully developed. Its fur is very soft and coarsens with age. The cub begins to crawl at 75 to 80 days;[11] mothers play with their cubs by rolling and wrestling with them. The cubs can eat small quantities of bamboo after six months, though mother’s milk remains the primary food source for most of the first year. Giant panda cubs weigh 45 kg (99 lb) at one year and live with their mothers until they are 18 months to two years old. The interval between births in the wild is generally two years.[96]

Initially, the primary method of breeding giant pandas in captivity was by artificial insemination, as they seemed to lose their interest in mating once they were captured.[97] This led some scientists to trying methods such as showing them videos of giant pandas mating[98] and giving the males sildenafil (commonly known as Viagra).[99] In the 2000s, researchers started having success with captive breeding programs, and they have now determined giant pandas have comparable breeding to some populations of the American black bear, a thriving bear species.[100][73]

In July 2009, Chinese scientists confirmed the birth of the first cub to be successfully conceived through artificial insemination using frozen sperm.[101] The technique for freezing the sperm in liquid nitrogen was first developed in 1980 and the first birth was hailed as a solution to the dwindling availability of giant panda semen, which had led to inbreeding.[102][103] Panda semen, which can be frozen for decades, could be shared between different zoos to save the species.[101][104] As of 2009, it is expected that zoos in destinations such as San Diego in the United States and Mexico City will be able to provide their own semen to inseminate more giant pandas.[103]

Attempts have also been made to reproduce giant pandas by interspecific pregnancy where cloned panda embryos were implanted into the uterus of an animal of another species. This has resulted in panda fetuses, but no live births.[105]

Human interaction

Early references

Main article: Mo (Chinese zoology)

In Ancient China, people thought pandas to be rare and noble creatures – the Empress Dowager Bo was buried with a panda skull in her vault. The grandson of Emperor Taizong of Tang is said to have given Japan two pandas and a sheet of panda skin as a sign of goodwill. Unlike many other animals in Ancient China, pandas were rarely thought to have medical uses. The few known uses include the Sichuan tribal peoples’ use of panda urine to melt accidentally swallowed needles, and the use of panda pelts to control menstruation as described in the Qin dynasty encyclopedia Erya.[106]

The creature named mo (貘) mentioned in some ancient books has been interpreted as giant panda.[106] The dictionary Shuowen Jiezi (Eastern Han Dynasty) says that the mo, from Shu (Sichuan), is bear-like, but yellow-and-black,[107] although the older Erya describes mo simply as a “white leopard”.[108] The interpretation of the legendary fierce creature pixiu (貔貅) as referring to the giant panda is also common.[109]

During the reign of the Yongle Emperor (early 15th century), his relative from Kaifeng sent him a captured zouyu (騶虞), and another zouyu was sighted in Shandong. Zouyu is a legendary “righteous” animal, which, similarly to a qilin, only appears during the rule of a benevolent and sincere monarch.[110]

In captivity

Main articles: Giant pandas around the world, List of giant pandas, and Panda diplomacy

See also: Category:Individual giant pandas

Pandas have been kept in zoos as early as the Western Han Dynasty in China, where the writer Sima Xiangru noted that the panda was the most treasured animal in the emperor’s garden of exotic animals in the capital Chang’an (present Xi’an). Not until the 1950s were pandas again recorded to have been exhibited in China’s zoos.[111] Chi Chi at the London Zoo became very popular. This influenced the World Wildlife Fund to use a panda as its symbol.[112] A 2006 New York Times article outlined the economics of keeping pandas,[113] which costs five times more than keeping the next most expensive animal, an elephant. American zoos generally pay the Chinese government $1 million a year in fees, as part of a typical ten-year contract. San Diego’s contract with China was to expire in 2008, but got a five-year extension at about half of the previous yearly cost.[114] The last contract, with the Memphis Zoo in Memphis, Tennessee, ended in 2013.[113]

In the 1970s, gifts of giant pandas to American and Japanese zoos formed an important part of the diplomacy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), as it marked some of the first cultural exchanges between China and the West. This practice has been termed “panda diplomacy“.[115] By 1984, however, pandas were no longer given as gifts. Instead, China began to offer pandas to other nations only on 10-year loans for a fee of up to US$1,000,000 per year and with the provision that any cubs born during the loan are the property of China. As a result of this change in policy, nearly all the pandas in the world are owned by China, and pandas leased to foreign zoos and all cubs are eventually returned to China.[116][117] As of 2022, Xin Xin at the Chapultepec Zoo in Mexico City, was the last living descendant of the gifted pandas.[118]

Since 1998, because of a WWF lawsuit, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service only allows US zoos to import a panda if the zoo can ensure China channels more than half of its loan fee into conservation efforts for giant pandas and their habitat.[119][120] In May 2005, China offered a breeding pair to Taiwan. The issue became embroiled in cross-Strait relations – due to both the underlying symbolism and technical issues such as whether the transfer would be considered “domestic” or “international” or whether any true conservation purpose would be served by the exchange.[121] A contest in 2006 to name the pandas was held in the mainland, resulting in the politically charged names Tuan Tuan and Yuan Yuan (from simplified Chinese: 团圆; traditional Chinese: 團圓; pinyin: tuanyuan; lit. ‘reunion’, implying reunification). China’s offer was initially rejected by Chen Shui-bian, then President of Taiwan. However, when Ma Ying-jeou assumed the presidency in 2008, the offer was accepted and the pandas arrived in December of that year.[122]

In the 2020s, certain “celebrity pandas” have gained a cult following amongst internet users, with dedicated fan accounts existing to keep tabs on the animals. Known as “giant panda fever” or “panda-monium”, individual pandas are known to get billions of views and engagements on social media, as well as product lines specifically emulating them.[123] At Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, certain of these “celebrity pandas” are known to garner hours-long lines specifically to see them.[123][124]

Conservation

The giant panda is a vulnerable species, threatened by continued habitat loss and fragmentation,[31][125] and by a very low birthrate, both in the wild and in captivity.[48] Its range is confined to a small portion on the western edge of its historical range, which stretched through southern and eastern China, northern Myanmar, and northern Vietnam. The species is scattered into more than 30 subpopulations of relatively few animals. Building of roads and human settlement near panda habitat, result in population declines. Diseases from domesticated pets and livestock is another threat. By 2100, it is estimated that the distribution of giant pandas will shrink by up to 100%, mainly due to the effects of climate change.[1] The giant panda is listed on CITES Appendix I, meaning trade of their parts is prohibited and that they require this protection to avoid extinction.[126] They have been protected and placed in category 1, by the 1988 Wildlife Protection Act.[127]

The giant panda has been a target of poaching by locals since ancient times and by foreigners since it was introduced to the West. Starting in the 1930s, foreigners were unable to poach giant pandas in China because of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War, but pandas remained a source of soft furs for the locals. The population boom in China after 1949 created stress on the pandas’ habitat and the subsequent famines led to the increased hunting of wildlife, including pandas. After the Chinese economic reform, demand for panda skins from Hong Kong and Japan led to illegal poaching for the black market, acts generally ignored by the local officials at the time. In 1963, the PRC government set up Wolong National Nature Reserve to save the declining panda population.[128]

The giant panda is among the world’s most adored and protected rare animals, and is one of the few in the world whose natural inhabitant status was able to gain a UNESCO World Heritage Site designation. The Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries, located in the southwest province of Sichuan and covering seven natural reserves, were inscribed onto the World Heritage List in 2006.[129][130][131] A 2015 paper found that the giant panda can serve as an umbrella species as the preservation of their habitat also helps other endemic species in China, including 70% of the country’s forest birds, 70% of mammals and 31% of amphibians.[132]

In 2012, Earthwatch Institute, a global nonprofit that teams volunteers with scientists to conduct important environmental research, launched a program called “On the Trail of Giant Panda”. This program, based in the Wolong National Nature Reserve, allows volunteers to work up close with pandas cared for in captivity, and help them adapt to life in the wild, so that they may breed, and live longer and healthier lives.[133] Efforts to preserve the panda bear populations in China have come at the expense of other animals in the region, including snow leopards, wolves, and dholes.[134] In order to improve living and mating conditions for the fragmented populations of pandas, nearly 70 natural reserves have been combined to form the Giant Panda National Park in 2020. With a size of 10,500 square miles, the park is roughly three times as large as Yellowstone National Park and incorporates the Wolong National Nature Reserve. Small, isolated populations run the risk of inbreeding and smaller genetic variety makes the individuals more vulnerable to various defects and genetic mutation.[135]

Population

In 2006, scientists reported that the number of pandas living in the wild may have been underestimated at about 1,000. Previous population surveys had used conventional methods to estimate the size of the wild panda population, but using a new method that analyzes DNA from panda droppings, scientists believed the wild population were as large as 3,000.[48] In 2006, there were 40 panda reserves in China, compared to just 13 reserves in 1998.[136] As the species has been reclassified from “endangered” to “vulnerable” since 2016, the conservation efforts are thought to be working. Furthermore, in response to this reclassification, the State Forestry Administration of China announced that they would not accordingly lower the conservation level for panda, and would instead reinforce the conservation efforts.[137]

In 2020, the panda population of the new national park was already above 1,800 individuals, which is roughly 80 percent of the entire panda population in China. Establishing the new protected area in the Sichuan Province also gives various other endangered or threatened species, like the Siberian tiger, the possibility to improve their living conditions by offering them a habitat.[138] Other species who benefit from the protection of their habitat include the snow leopard, the golden snub-nosed monkey, the red panda and the complex-toothed flying squirrel.[139]

In July 2021, Chinese conservation authorities announced that giant pandas are no longer endangered in the wild following years of conservation efforts, with a population in the wild exceeding 1,800.[139][140] China has received international praise for its conservation of the species, which has also helped the country establish itself as a leader in endangered species conservation.